Dreams of a Summer Night: Scandinavian Painting at the Turn of the Century

A Review of The exhibition Dreams of a Summer Night: Scandinavian Paintings at the Turn of the Century, at the Hayward Gallery in London from 10 July to 5 October 1986

The exhibition Dreams of a Summer Night: Scandinavian Paintings at the Turn of the Century, at the Hayward Gallery in London from 10 July to 5 October 1986, exhibited works of artists represented in the Nationalmuseum, Nordiska Museet, Prins Eugens Waldermasudde and Thielska galleriet. The London exhibition imparted an impression of immobility, with nature as the dominant force. In The Blind Girl (1896 to 1898) and In his Eyes I saw Death (1867) by the Danish artist Ejanar Nielsen (1872-1956), the figures were somber, passive and statuesque. In Autumn (1891) and Summer Evening at Kviteseid (1893), by the Norwegian painter Erik Werensild (1855-1938), the technique was often labored and exaggeratedly naturalist They portrayed a society lacking in dynamism, dramatised so forensically in the plays of Ibsen (1828-1906), but this did not explain the sadness and sense of immobility, perhaps caused by the contemplation of nature, in After Sunset (1886) and Summer Night (1886) by Kitty Kielland (1843-1914) and Winter Night in Rondane (1901) and Summer Night (1899) by Harald Sohlberg (1869-1935), the cover image of the catalogue, displaying the warm reflection of the sun after it has left.

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was different, his work impregnated with the influence of symbolism.

Edvard Munch was in Paris from 1889-1892, the great years of Symbolism. Indeed, Ernest Raynaud, the authority on French Symbolism, called 1891 la date heureuse du symbolisme. Solitary and isolated though Munch was, he was almost certainly familiar with the fundamental ideas of Symbolism. His links with Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, and Maeterlink seem to be well documented, and he adopted the new spiritualism of Paris quite spontaneously. As early as 1889, he painted Inger on the Beach, and in 1890 his self-portrait Night in St Cloud, works which, with their inward sensitivity and deep melancholy, can be considered turning points in the Scandinavian art of the end of the century. (Sarajas-Korte 42)

In The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1900), Arthur Symons (1865-1945) set out the aims of the symbolist writers in Paris with whom Munch associated.

There is such a thing as perfecting form so that form may be annihilated. All the art of Verlaine is in bringing verse to a bird's song, the art of Mallarmé in bringing verse to the song of an orchestra. In Villier de l’Isle-Adam drama becomes an embodiment of spiritual forces, in Maeterlink not even their embodiment, but the remote sound of their voices. It is all an attempt to spiritualise literature, to evade the old bondage of rhetoric, the old bondage of exteriority. Description is banished that beautiful things may be evoked, magically; the regular beat of verse is broken in order that words may fly, upon subtler wings. Mystery is no longer feared, as the great mystery in whose midst we are islanded was feared by those to whom that unknown sea was only a great void. We are coming closer to nature, as we seem to shrink from it with something of horror, disdaining to catalogue the trees of the forest. And as we brush aside the accidents of daily life, in which men and women imagine that they are alone touching reality, we come closer to humanity, to everything in humanity that may have begun before the world and may outlast it. Here, then, is this revolt against exteriority, against rhetoric, against a materialistic tradition; in this endeavour to disengage the ultimate essence, the soul, of whatever exists and can be realised by the consciousness; in this dutiful waiting upon every symbol by which the soul of things can be made visible; literature, bowed down by so many burdens, may at last attain liberty, and its authentic speech. In attaining this liberty, it accepts a heavier burden; for in speaking to us so intimately, so solemnly, as only religion has hitherto spoken to us, it becomes itself a kind of religion, with all the duties and responsibilities of the sacred ritual. (9-10)

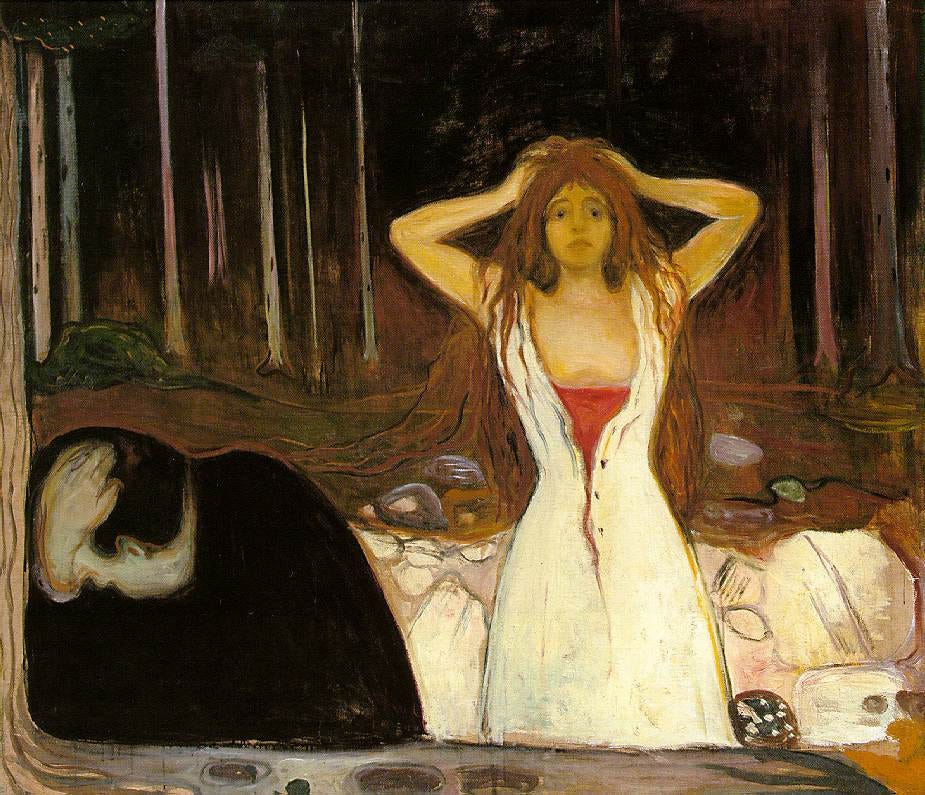

The painting Ashes (1894), in particular, captured the distance between the bewildered young woman and the despairing man against the backdrop of the Nordic forest sunk in darkness.

Edvard Munch’s depictions of femmes fatale were more personal and obsessive. The imagery long associated with Medusa was reenergized by nineteenth-century anxieties about the shifting, ambiguous boundaries of sexualized women, and Munch’s female figures draw upon this tradition. In images such as Vampire (1893) and Ashes (1894), women’s serpent black hair winds around their prey. Munch’s full-length depictions of women never show their feet; instead their dresses swirl sinuously (wrapping around male partners it possible), like the skirts of the Medusa so vividly described by Hugo. (Connelly 138)

Munch’s simple range of colours with heavy use of black to darken the ochres and greens fixes the gaze on the red petticoat and unbuttoned white dress of the young woman.

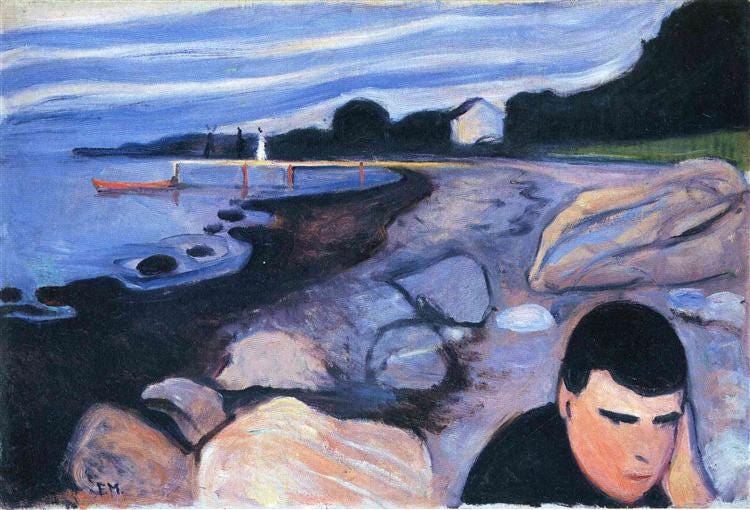

The message is clear. Love is dead, burned to ashes, reduced to loneliness and despair. Behind the erotic content lies a deathly fear of annihilation by woman. In the lithographed version of the picture (1896), the log in the foreground is a smoking heap of ashes. Munch himself commented: ‘I felt our love lying on the ground like a heap of ashes’. The design of Ashes is even more simplified than, for example, that of Melancholy (No. 57). There is a greater fluidity of line and the palate is richer and more powerful, with more expressive contrasts. The symbolic value of colours is consciously explored (Tone Skedsmo, Dreams of a Summer Night 196).

In Munch’s work form is critical; in Inger on the Beach (1889) and Melancholy (1891-1892) reality takes second place to the unity of form between nature and the individual. He shapes his own inner vision. “The artist who is above all things an artist cultivates a little choice corner of himself with elaborate care; he brings miraculous flowers to growth there, but the rest of the garden is but mown grass or tangled bushes” (Symons, The Symbolist Movement 69).

In The Forest (1892) and Still Water (1901), the Swedish painter Prince Eugen (1865-1947) conveys the impression of the reception rather than the forming of sensory input, a representation of isolation and leisure.

The Danish painter Vilhelm Hammerschøi (1864-1916) in Study of a Woman (1888) and The Collector of Coins (1904), achieves a severe simplicity of subject, with a single figure described in a limited range of colours, reminiscent of the mastery displayed in the subdued interiors of Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). The effect achieved by Hammerschøi is based on subtle tonal variations and contrasting simple forms as in A Farm at Refsnæs (1900) and Five Portraits (1901).

In contrast, the Swedish painter and dramatist August Strindberg (1849-1912) in his two 1892 paintings Stormy Sea. Broom Buoy and Stormy Sea. Buoy without Top Mark and in his 1901 Inferno-Painting sought to express violent emotions through the use of wild and turbulent brush strokes.

The overwhelming impression of the Exhibition was one of loneliness and individuality, with occasional glimpses outside the bourgeois world into a peasant collectivism represented by wild dancing and vitality, most notably in Midsummer Dance (1897) by the Swedish painter Anders Zorn (1860-1920).

Works Cited

Connelly, Frances S. The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture: The Image at Play, Cambridge UP, 2012.

Sarajas-Korte, Salme. “Aspects of Scandinavian Symbolism.” Dreams of a Summer Night: Scandinavian Painting at the Turn of the Century. Edited by Leen Ahtola-Moorhouse, Carl Tomas Edam and Birgitta Schreiber, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986, pp. 39-53.

Symons, Arthur. The Symbolist Movement in Literature. William Heinemann, 1899.