Edmund Burke’s aims in publishing Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

This paper examines three critical aspects of Burke's beliefs, principles, and political judgment at the time of the outbreak of the French Revolution.

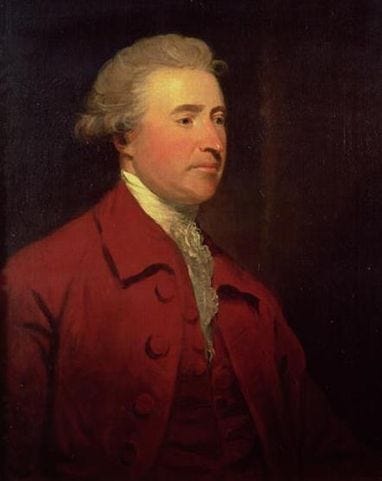

By James Northcote - http://www.bridgemanartondemand.com/art/99202/Portrait_of_Edmund_Burke, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6830598

1. Introduction

In a letter to Philip Francis dated 20th February 1790, replying to his criticisms of an early draft of the Reflections, Burke wrote: ‘But I intend no controversy with Dr Price or Lord Shelburne or any other of their set. I mean to set in a full view the danger from their wicked principles and their black hearts; I intend to state the true principles of our constitution in Church and state - upon Grounds opposite to theirs’ (1967:92).

In this declaration of intent, Burke signals the motivating forces that led him to publish the Reflections on 1st November 1790: to sound a public alarm against the dangers he perceived would arise in Great Britain and the rest of Europe from any support or toleration for the principles and actions animating the French revolution and to set out and defend his views on the principles of the British constitution against those expressed by Dr. Price in his Discourse on the Love of our Country delivered on November 4th, 1789 and ‘in particular to demolish the claim that the English Revolution of 1688 might be read in such a way as to provide justification for the French Revolution of l789, and thus to assimilate the former event to the latter’ (Pocock:282).

However, it would be over-simplistic to rely on Burke's pronouncements alone in seeking to understand his motivations and ambitions in publishing the Reflections since it would not give sufficient weight to the rich complexity of Burke's personal, political, and intellectual background and the specific personal and political aspects of his situation in 1790. In this paper, I shall brief1y examine three critical aspects of Burke's beliefs, principles, and political judgment at the time of the outbreak of the French Revolution and examine how they assist in explaining different and less public strands in his motivation to publish the Reflections: his views on religion and in particular his attitude to Dissenters; the state of his political career and inf1uence in 1789 as a semi-detached member of the Foxite Whigs; and finally how he saw the publication of the ideas and arguments in the Reflections as a necessary step to maintain and affirm the consistency of his political philosophy in the face of the danger that, on the basis of his previous writings on liberty in the context of the American Revolution, he would be 'reckoned among the approvers of certain proceedings in France’ (Reflections:85). Such consistency was an indispensable requirement for Burke since as he stressed, referring to himself, in An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs published in 1791: ‘I believe, if he could venture to value himself upon anything, it is on the virtue of consistency that he would value himself the most. Strip him of this, and you leave him naked indeed’. (1907:30).

I shall argue in conclusion that, in setting the publication of the Reflections in this context, one can appreciate more fully the passion and conviction that is expressed throughout the work and which ensured its success in propagating Burke’s political ideas both during his remaining years and to the present day.

2. Burke: Religion and Dissenters

Burke’s relationship to Catholicism is contested. Born in Dublin in 1730, Burke’s mother was Catholic while his father was a member of the Church of Ireland, although it is possible he had conformed in March 1722 in order to be admitted as an attorney (Lock 1998:4). Burke himself was educated at a Catholic, then Quaker, school and at Trinity College, Dublin: ‘founded by Queen Elizabeth I in 1592, to train clergy for the Church of Ireland’ (Lock 1998:29-30). His wife, Jane Nugent, was a Catholic from an Ulster Catholic family (O'Brien 1992:38). Burke’s attitude to religion is set out in a letter to an unknown correspondent dated 26 January 1791: ‘I have been baptised and educated in the Church of England; and have seen no cause to abandon that communion. When I do, I shall act upon conviction or my mistake. I think that Church harmonises with our civil constitution, with the frame and fashion of our Society, and with the general Temper of the people. I think it is better calculated, all circumstances considered, for keeping peace among the different sects, and affording to them a reasonable protection, than any other system’. (Correspondence, VI. 215).

As O'Brien has pointed out (Reflections, 29), these reference to the Church of England are ‘cool and politic, provisional and contingent’ and he has argued (1992:82-84) that Burke’s support for the Anglican church was dictated by political necessity and that he remained sympathetic to, and active in support of, the cause of the Irish Catholics throughout his career. Burke certainly had reasons to dread anti-Catholicism: he was throughout his career subject to slurs that he was a crypto-catholic, most notably from the Duke of Newcastle on his appointment as Rockingham's secretary, and his house and personal safety was threatened during the anti-Catholic Gordon riots in June 1780 due to his support for a Bill to extend to Scottish Catholics the benefits of the English Catholic Relief Act of 1778.

It is in this context that Burke’s attitude to the Dissenters and, in particular to the writings of Dr. Price, needs to be examined. While Burke had no hostility to the Dissenters as a body, and indeed was not in principle opposed to the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts (Correspondence, VI 101-104), he considered the maintenance of an established Church a crucial element in the stability of the state and society. The attack on the rights and property of the established church by the French revolutionaries was one of the principal targets of Burke's polemic in the Reflections, since he saw it as an ‘outrage on all the rights of property’ (Reflections, 207). However, it was not Price’s support for the repeal of the Test Acts in his Discourse that would have alarmed Burke, but rather his anti-Catholicism expressed in such phrases as: ‘Set religion before them as a rational service consisting not in any rites and ceremonies, and that gloomy and cruel superstition will be abolished which has hitherto gone under the name of religion, and to the support of which civil government has been perverted’ and ‘It helps to prepare the minds of men for the recovery of their rights, and hastens the overthrow of priestcraft and tyranny .. oppressors of the world .. they have appointed licensers of the press, and, in Popish countries, prohibited the reading of the Bible’ (Discourse, 182).

As O'Brien (1992:395-6) has pointed out, this anti-Catholic strain in Price's sermon, and in the accompanying resolution carried by the Revolution Society, provided Burke with a powerful emotional motivation to write the Reflections: ‘The link between Protestant zealotry and British zeal for the French Revolution was real, and understandably alarming to Edmund Burke’ (1992:396). For Burke an established church provided security for all faiths; one of his unstated aims in publishing the Reflections was to demolish the arguments used to justify the attack on the established church in France so that they could not be successfully propagated by anti-papist dissenting Ministers in Britain.

3. Burke and the Foxite Whigs

By the time Burke started work on the Reflections in early 1790, aged 60, his political influence within his party had been in steady decline since the death of Rockingham in 1782; this process accelerated after the crushing defeat inflicted by William Pitt on the Fox-North Coalition in the general election of 1784 and which led to Burke’s loss of office as Paymaster-General of the Forces. During the subsequent years, he became an increasingly isolated figure within the Whig opposition led nominally by the Duke of Portland but dominated by Charles Fox and, increasingly over the period, his followers Sheridan and Grey. In a letter to the Earl of Charlemont dated 10th July 1789, days before the storming of the Bastille, Burke wrote in a resigned tone: ‘My time of Life, the length of my Service, and the Temper of the publick, renderd it very unfit for me to exert myself in the common routine of the opposition: Turpe senex Miles. There is a time of life, in which, if a man cannot arrive at a certain degree of authority, derived from a confidence from the Prince or the people, which may aid him in his operations, and make him compass useful Objects without a perpetual Struggle, it becomes him to remit much of his activity.’ (Correspondence VI:1).

As has been remarked (Harris 1993:300-302; Correspondence VI:xiii-xiv), the publication of the Reflections provided Burke with an opportunity to arrest this decline into semi-retirement and re-establish himself as the defender of true Whig principles. He rightly perceived that it provided him with an issue that would enable him to re-establish a separate political identity in opposition to the Foxite Whigs. As early as February 1790, on the occasion of the Debate on the Army Estimates in the House of Commons, the support of Fox and Sheridan for the principles of the French Revolution had been made clear, and Burke took the opportunity to publish his speech on the 9th February to the House of Commons clearly setting out his opposition to the same principles – even if that meant opposition to the leader of his party (Harris 1993:311-320). The fact that Wiliam Pitt, Fox’s most hated political rival, applauded and congratulated Burke on his speech (1993:320) must have confirmed to Burke that he had crossed a political rubicon – a fact irrevocably confirmed by Burke’s expulsion by the Foxites from their party in the aftermath of the debate on the Quebec Bill in April 1791 that was turned by Burke into a debate between himself and Fox on the merits of the French constitution.

Philip Francis wrote to Burke on 19th February: ‘The mischief you are going to do yourself is, to my apprehension, palpable. It is visible. It will be audible. I sniff it in the wind. I taste it already. (Correspondence VI:87). In his stinging reply to Francis on 20th February, Burke showed he fully intended by publication of the Reflections to oppose the ‘prejudices and inclinations of many people’(VI:89). Burke had by then taken the decision to publish and a rupture with Fox, and thereby an implicit alignment with Pitt, was a price he was more than willing pay in order to regain for himself the ‘degree of authority, derived from a confidence from the Prince or the people’ he had only months earlier despaired of ever again achieving. As Burke wrote in 1791 in An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs commenting on the publication of the Reflections and his subsequent expulsion from his party: ‘But the matter stands exactly as he wishes it. He is more happy to have his fidelity in representation recognized by the body of the people, than if he were to be ranked in point of ability (and higher he could not be ranked) with those whose critical censure he had the misfortune to incur’ (1907:6).

4. Burke and Liberty

‘The destruction of the Feudal System has deprived pride of its power and Aristocracy of it’s authority, and it is as probable, that those who pulled down the Bastille should build it up again and consent to be shut up in it, as that a Counter revolution should be worked’ (Correspondence VI:72). When Burke read these words in a letter from his friend Thomas Paine, and the famous author of Common Sense, on 17th January 1790 describing the situation in France, at the time he had just read the sermon of Dr. Price and was embarking on the Reflections, he received a powerful reminder of the urgency and necessity of the task he had set himself.

There was a real risk that in failing to record publicly his opposition to the French Revolution his name and reputation might be associated with principles and actions he abhorred on the basis of his writing and speeches on liberty and the American Revolution and his correspondence with men such as Paine, who had enthusiastically transferred their support for Liberty from one revolution to the other. Such concerns were not fanciful as Paine later confirmed in his preface to the Rights of Man, first published in February 1791 in reply to the Reflections: ‘From the part Mr. Burke took in the American Revolution, it was natural that I should consider him a friend to mankind; and as our acquaintance commenced on that ground, it would have been more agreeable to me to have had cause to continue in that opinion, than to change it’. The Reflections were published by Burke to ensure Paine had every cause not to continue in that opinion.

In his speech moving his Resolution for Conciliation with the Colonies to the Commons on March 22nd 1775, Burke identified the strength of the American colonists’ attachment to Liberty: ‘They are therefore not only devoted to Liberty, but to Liberty according to English ideas, and on English principles. Abstract Liberty, like other mere abstractions, is not to be found. Liberty inheres in some sensible object; and every nation has formed to itself some favourite point, by way of eminence becomes the criterion of their happiness ... Their love of liberty, as with you, fixed and attached on this specific point of taxing’ (1993:222). For Burke, liberty needed social attachment or else it would lead to anarchy and lawlessness as had been demonstrated by the French revolutionaries. He explained in detail the type of liberty to which he was attached in his first letter to Depont in November 1789: ‘It is not solitary, unconnected, individual, selfish Liberty. As if every Man was to regulate the whole of his Conduct by his own will. The Liberty I mean is social freedom. It is the state of things in which Liberty is secured by the equality of Restraint; A Constitution of things in which the liberty of no one Man, and no body of Men and no Number of men can find Means to trespass on the liberty of any Person or any description of Persons in the Society. This kind of Liberty is indeed but another name for Justice, ascertained by wise Laws, and secured by well constructed institutions’ (Correspondence VI. 42).

It was this conception of liberty that Burke had argued in 1775 was shared by Englishmen and the American colonists and that as long as the British Government had ‘the wisdom to keep the sovereign authority of this country as the sanctuary of liberty’ (1993:265) it would ensure the colonists remained loyal. This is the conception of liberty that Burke defends in the Reflections: ‘I should therefore suspend my congratulations on the new liberty of France, until I was informed how it had been combined with government; with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with morality and religion; with peace and order; with civil and social manners’ (91-92). Burke spent a large portion of the Reflections arguing that the ‘new liberty of France’ fulfilled none of these requirements.

Burke was later to record, in An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, the consistency of his views on liberty over the length of his Parliamentary career that culminated in the views expressed in the Reflections: ‘‘He told the House, upon an important occasion and pretty early in his service, that ‘being warned by the ill effect of a contrary procedure in great examples, he had taken his ideas of liberty very low; in order that they should stick to him, and that he might stick to them to the end of his life’. The liberty to which Mr. Burke declared himself attached is not French liberty. That liberty is nothing but the rein given to vice and confusion’’ (1907:33-34).

5. Conclusion

The three specific threats and opportunities which Burke identified in late 1789 and early 1790 as inevitably associated with the French revolution and its supporters - anti-Catholic propaganda, the split in the Whig party, and the attempt to assimilate Burke’s support for liberty in the context of the American revolution to that of the French - should not be seen as distinct from the other, more overt, aims he was pursuing in publishing the Reflections. Rather these strands overlapped and reinforced each other and contributed to weave the rich fabric that is the Reflections. Without this diversity of purpose, the Reflections would have perhaps been a more structured and less dense and rhetorical work, but also less effective in achieving the multiple ends Burke was pursuing.

Bibliography

Burke’s Works

The Correspondence of Edmund Burke, Volume VI, edited by Alfred Cobban and Robert A. Smith (Cambridge University Press 1967).

Pre-Revolutionary Writings, edited by Ian Harris (Cambridge University Press 1993).

Reflections on the Revolution in France, edited by Conor Cruise O'Brien (Penguin 1969).

The Works of Edmund Burke, Vol. V, with an Introduction by F.W.Rafferty (Oxford University Press 1907)

Secondary Sources

Edmund Burke, Volume 1, F.P. Lock (Oxford University Press 1998)

The Emergence of the British Two-Party System 1760-1832, Frank O'Gorman (Edward Arnold 1982)

The Great Melody, Conor Cruise O'Brien (Sinclair-Stevenson 1992)

Richard Price: Political Writings, edited by D.O.Thomas (Cambridge University Press 1991).

Thomas Paine: Rights of Man, Introduction by Eric Foner (Penguin 1985)

Virtue, Commerce and History, J.G.A.Pocock (Cambridge University Press 1985)