Jules Pascin and George Grosz: Selected Satirical Works

The influence of Pascin's illustrations for the satirical magazine Simplicissimus on Grosz's early drawings

Jules Pascin (1885-1930)[1] and George Grosz (1893-1959)[2] met in Paris in 1913 where Pascin had moved in 1905. While Pascin was already a recognized artist through his drawings for the German satirical journal Simplicissimus, founded in Munich in 1896 by Albert Langen (1869-1909), Grosz was experiencing the Parisian art scene as an impressionable twenty-year old while studying at the Académie Colarossi. The two men were markedly different in temperament and artistic intent: Pascin apolitical and a lifelong hedonist, Grosz a formative member of the Berlin Dada movement and a committed political activist during the 1920s, having joined the German Communist Party in 1918-19.[3] Pascin and Grosz formed a friendship which lasted intermittently until Pascin’s suicide in 1930 (Grosz: 92, 183, 185, 254). They shared a number of artists as friends, notably Rudolf Grossmann (1882-1941),[4] who from 1914 contributed to Simplicissimus and who had met Pascin in Paris as part of the Café du Dôme circle of German artists.[5]

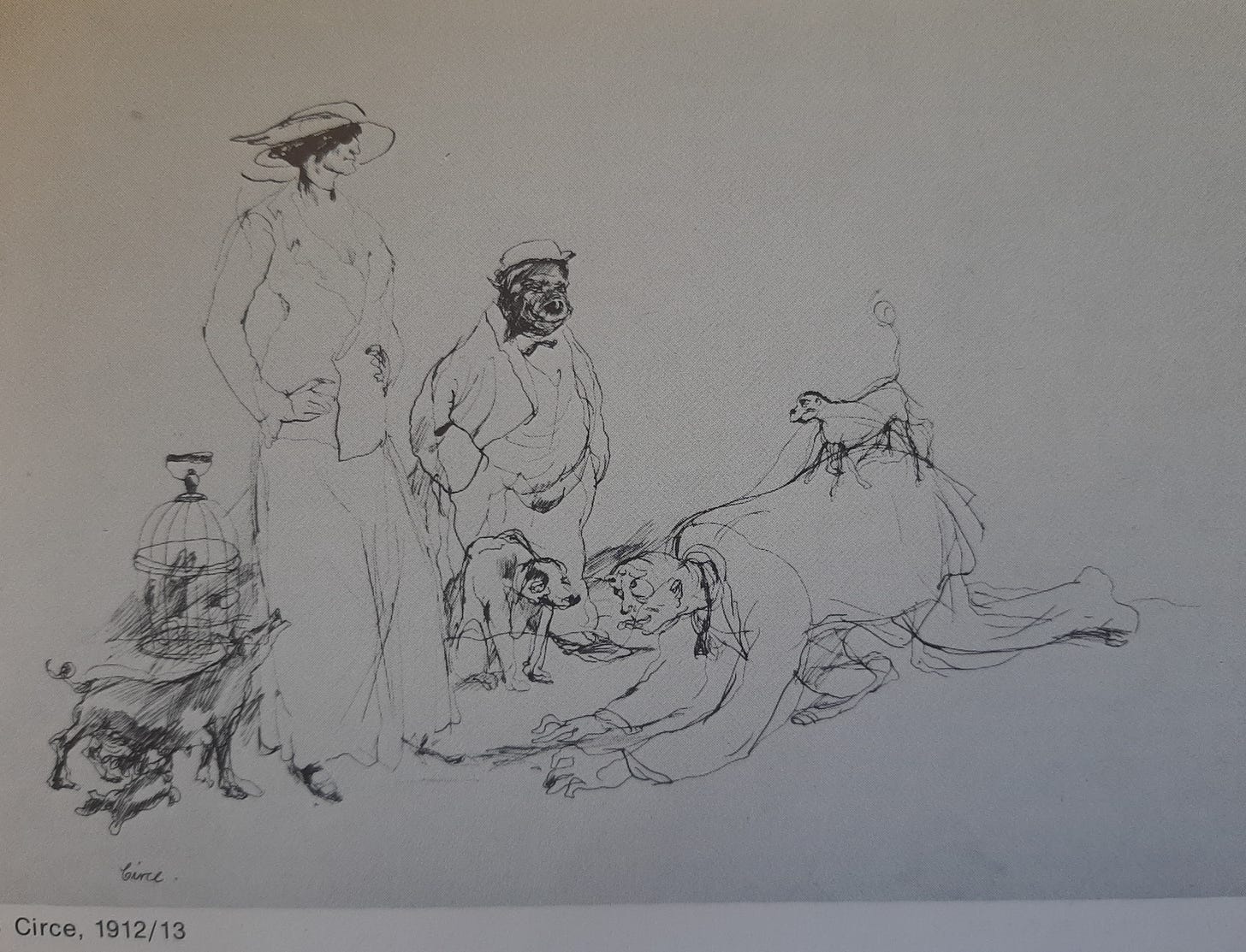

This study will focus on works Pascin produced for Simplicissimus from March 1905 to 1914, when Pascin left Paris for the United States to avoid conscription in the Bulgarian army.[6] On his arrival in Paris, Grosz would already have been familiar with Pascin’s drawings as an avid reader of Simplicissimus (Flavell 278), from 1925 himself contributing to the magazine. The focus on Grosz will be on drawings in the period 1911 to 1920, Circe (1912-1913), Das Ende des Weges (Aus Nahrungssorgen) [The End of the Road (Out of Fear of Starvation)] (1913), Männer am Biertisch (1916), Lustmord auf der Akerstrasse (1916/1917) and illustrations from Phantastische Gebete (1920), a text by fellow Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck (1892-1974).[7]

Pascin and Grosz in their graphic works of this period shared a thematic focus, notably on the representation of the grotesque, sexual perversion and social satire.

The Grotesque

“As visual forms, grotesques are images in flux: they can be aberrant, combinatory, and metamorphic” (Connelly 2). Pascin’s in several of his Simplicissimus drawings represents the grotesque through sinister creatures that can be related to the Kallikantzari, a goblin-like creature of ill-will featuring in Anatolian and south-east European folklore, which would have been familiar to him through his childhood spent in Bulgaria and Romania, after his family’s move to Bucharest in 1892.

Whilst descriptions of them [Kallikantzari] vary, in common are the characteristics of extreme ugliness and thinness. Each, moreover, is in some way deformed: ‘Some are lame, some are one-eyed, one-legged, bow-legged, with twisted mouths, faces, hands, some are hunchbacked, wrinkled; and briefly, all of the defects and infirmities you will find upon them.’ (Loosli 126)

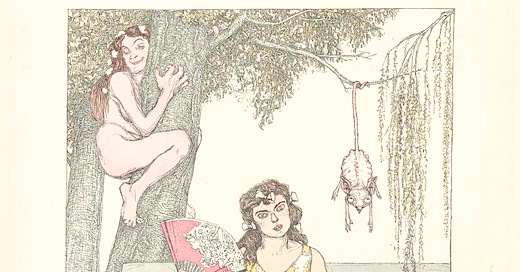

A notable example of Pascin’s use of the grotesque is his drawing Im Wonnemond (In the Month of May) (Simplicissimus Year XII, June 1908, No. 20, p. 499).[8]

The two grotesque creatures represented match the Kallikantzari images of folklore and destabilise the viewer’s perception of the scene by introducing discordant elements.

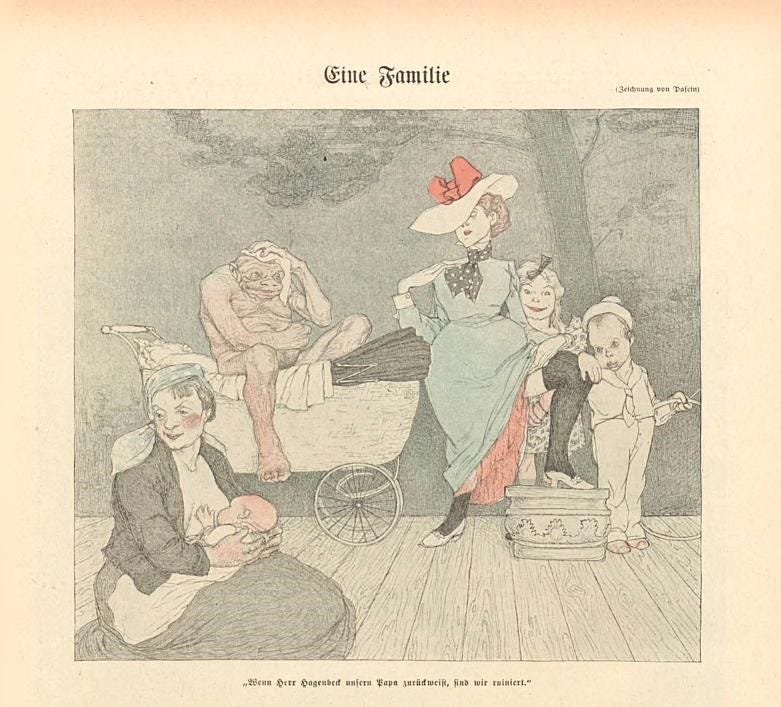

In Eine Familie (Simplicissimus Year X, October 1905, No. 28, p. 330), the family is desperate for the purchase of their father by the Hamburg zoo to save them from financial ruin.[9]

Pascin uses the portrayal of the father in apelike form in a baby’s carriage and the salubrious gesture of the young girl’s hand on her mother’s thigh to satirise the family as an institution.

Grosz’s use of animal morphology is driven by his agenda of political satire but also his profoundly pessimistic vision of the human condition.

Similar to the theme of physical degeneration is Grosz's evocation of animal forms in his city scenes. Far from implying a sense of basic closeness with nature, Grosz's message is that, in the city, humans have reduced themselves to barbarism. With bestial features, the artist dehumanizes his characters, banking on the assumption that animals are of a lower realm. At the same time, however, he makes the needs of the body equalizing qualities, using fundamental human-nature as a mechanism to balance class hierarchies. (Boetzkes 216)

In Circe, Grosz’s representation of the monkey on the back of the kneeling man recalls the morality tale The Old Man of the Sea, the fifth in the Stories of Sinbad. “Strindberg springs to mind when, in Circe, Grosz draws the woman as dominating the man who grovels at her feet, the monkey on his back an additional caustic satiric comment on his situation” (Schneede, Leben und Werk 20).

In Männer am Biertisch, Grosz’s transfiguration of the two men at the table into brutal zoomorphic forms depicts his cynical view of men’s debased nature.

Further examples of Grosz’s use of zoomorphic images are two drawings reproduced in Phantastiche Gebete (Huelsenbeck 15, 27), where the contributions of Grosz are: “illustrations that are only partly political; primarily they express the irrational, bestial condition of man” (Knust 230).

Sexual Perversion

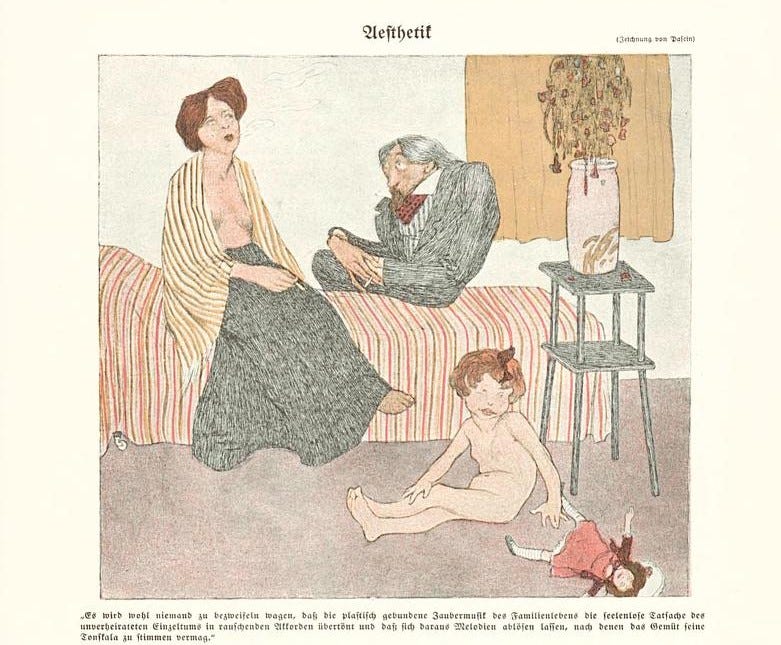

Pascin’s representation of sexuality was the predominant theme in his art. There were no moral boundaries to his observant eye. In his early drawings for Simplicissimus, the constraints of publication tempered his representation, but his mordant view of bourgeois morality and family life emerge in the caustic drawing Aesthetik (Year XI, February 1907, No. 47, p. 764).[10]

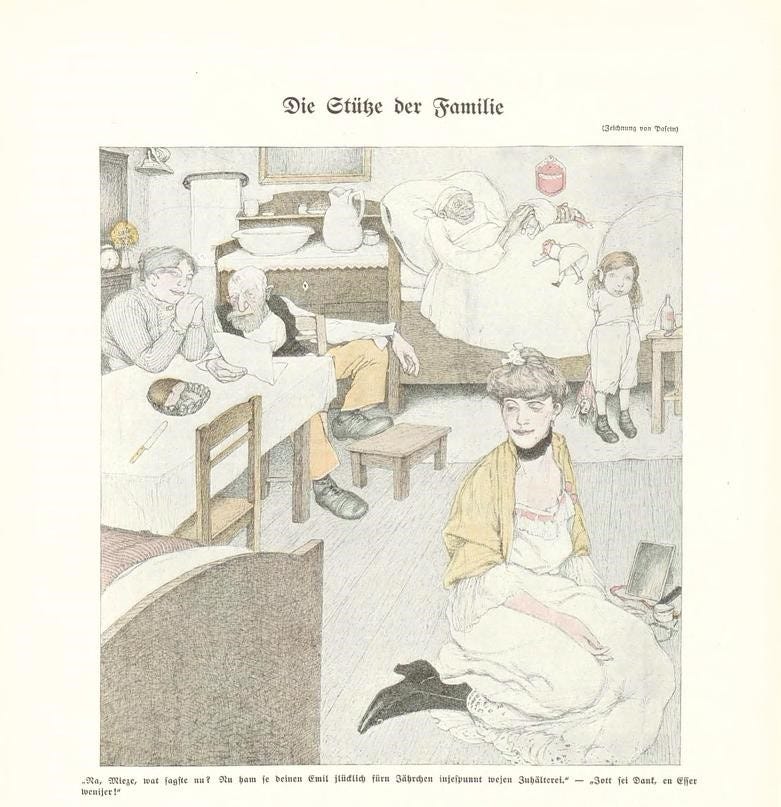

Pascin’s representation of sexual perversity was perhaps influenced by his own precocious sexual experiences in childhood (Levy-Kuentz 19-20), but more proximately was the time he spent in Berlin from 1904 to 1905, where he would have experienced the rampant prostitution (Ankum 210) and famed decadence of Berlin as the “Whore of Babylon” (Smith 3), as demonstrated in his illustration Die Stütze der Familie (The Bread-Winner) (XI Year, October 1906, No. 29, p. 459)[11] and Variété (X Year, April 1905, No. 2, p. 14).[12]

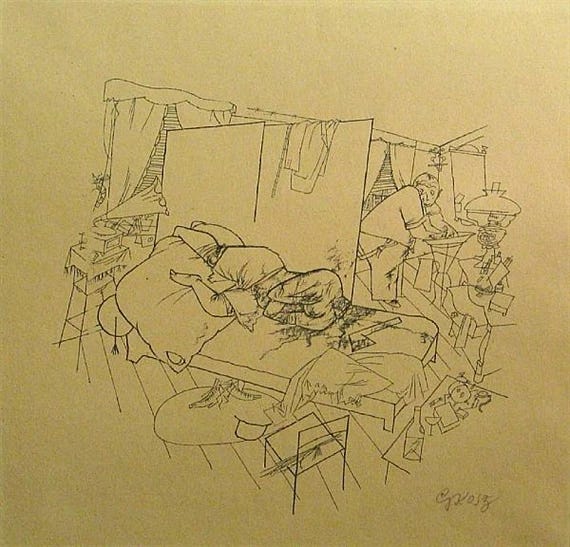

Grosz’s childhood erotic experiences, notably when he witnessed a friend’s Aunt slowly undressing (Grosz 21-29), may also have been formative in his depiction of sexual perversion. Grosz’s experiences during his service in WWI are considered pivotal, notably in his series of Lustmord drawings and paintings, such as Lustmord in der Akerstrasse (1916/1917).

As both Tatar and Irwin have noted, there is a difference between the drawings and paintings that Grosz produced between 1912-1913 and those after the war. The postwar Sexual Murders become all the more explicit in their depiction of violence and brutality. This profound violence … is inextricably linked to Grosz’s traumatic war experience.” (Tsampouraki 3)

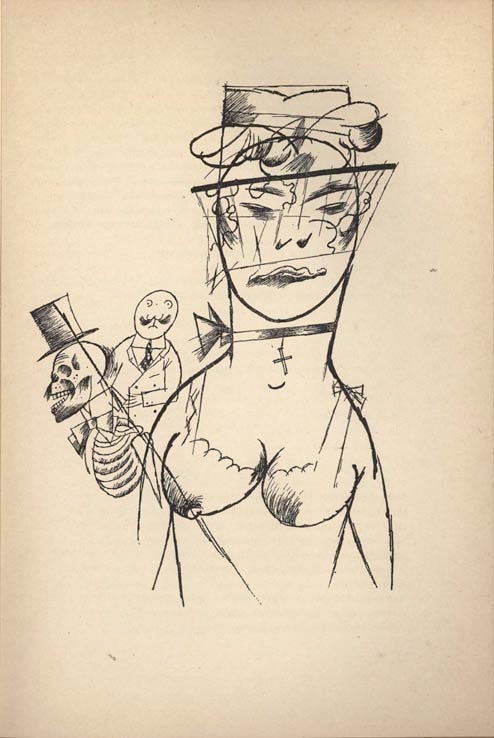

Grosz’s art following his WWI service took a radically different path from Pascin, who spent the war in the United States, and whose art is free of violent imagery. Grosz’ linkage of sex and death is evident in this illustration in Phantastiche Gebete (17).

As Pascin, Grosz represented the prevalence of prostitution in Berlin pre-WWI, as in this image of a man propositioning a prostitute with two leering men looking on (Phantastiche Gebete (23).

Social Satire

While Pascin was profoundly apolitical in his art and life, his drawings for Simplicissimus show a talent for biting social satire. Drawing upon his Eastern European heritage, Pascin satirized bourgeois morality and in particular the institution of the family. In Nach dem Kongreß (Year X, September 1905, No. 27, p. 318),[13] he parodies the hypocrisy of delegates to the 1905 Sittlichkeitskongress that took place in Magdebourg, a conference of associations combating female trafficking, by showing two men returning to their dysfunctional family.

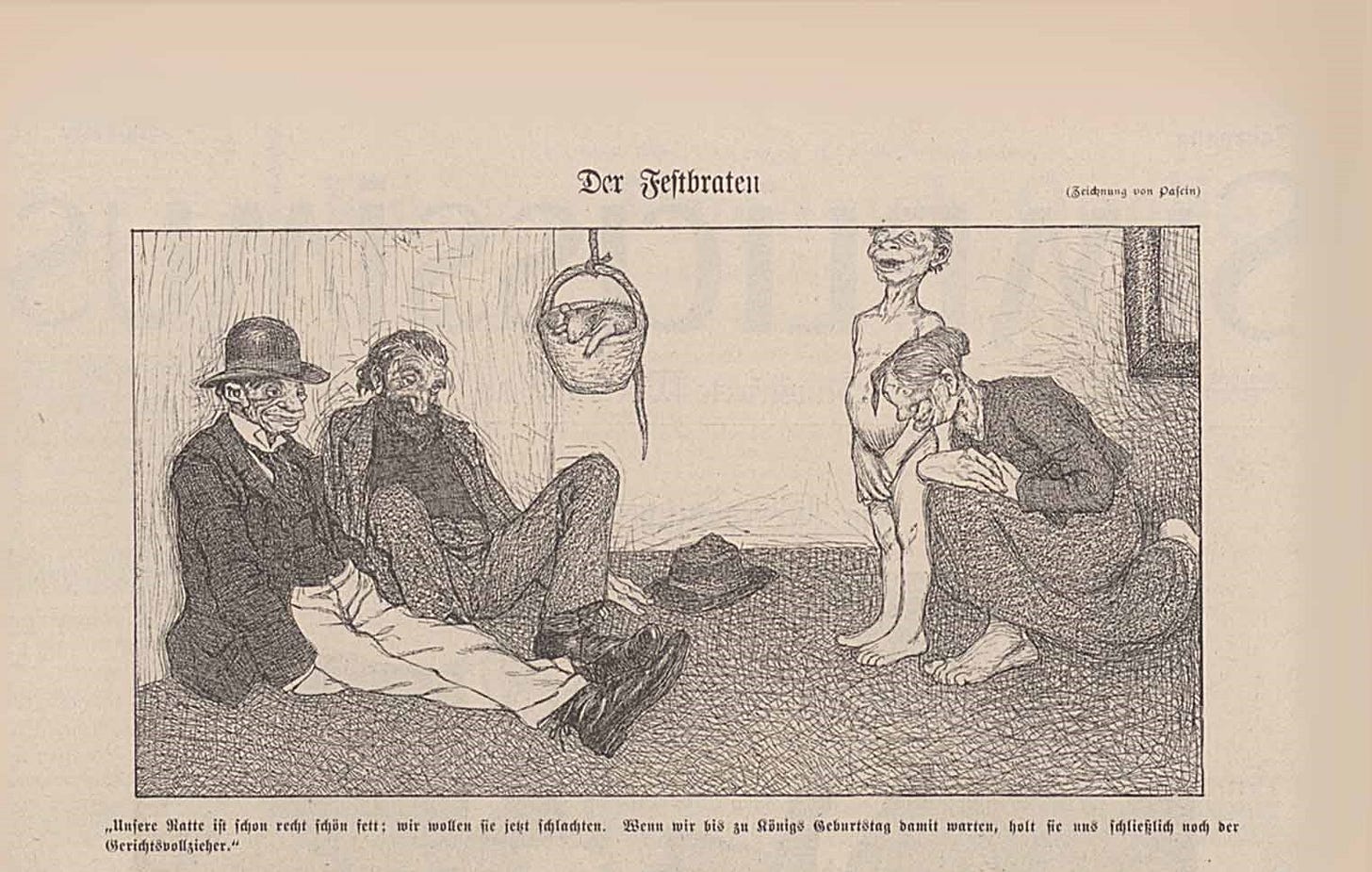

Hunger and poverty are further targets for Pascin’s satire, as in Eine Familie and Der Festbraten [The Holiday Roast] (Year IX, March 1905, no. 51, p. 502).[14]

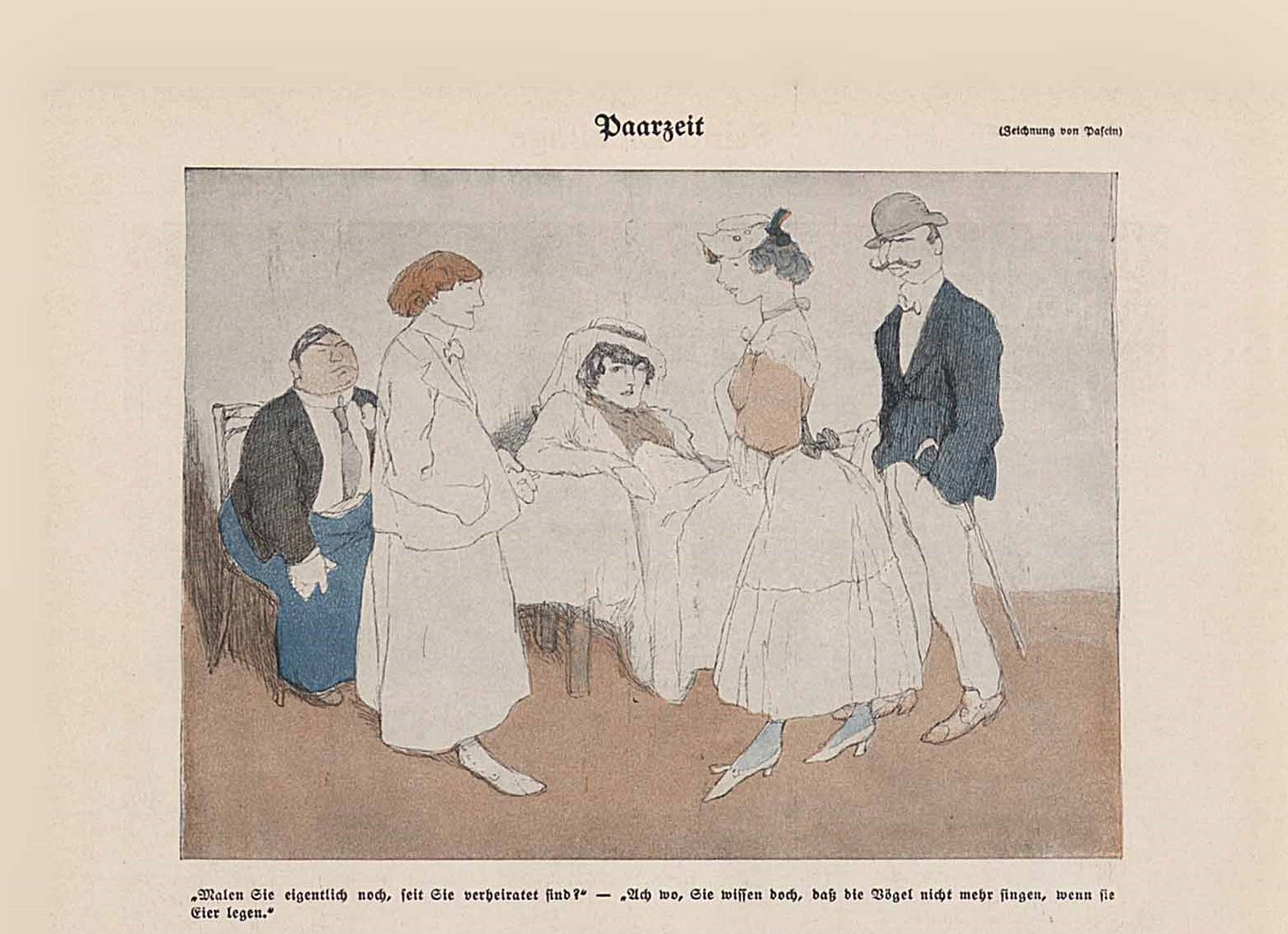

The institution of marriage and the career constraints it placed on women is satirized in Paarzeit Year XII, March 1908, No. 51, p. 838.[15]

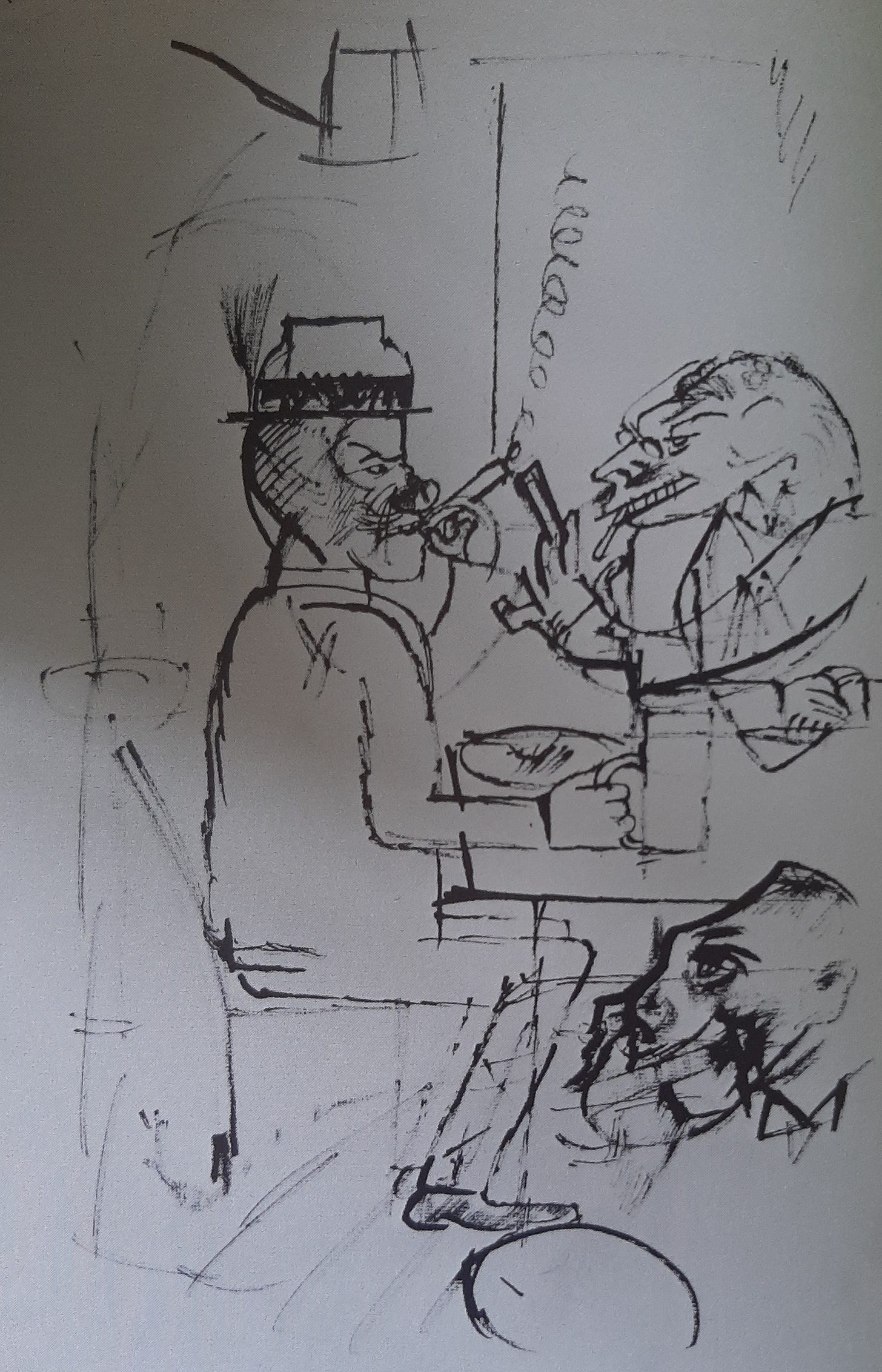

Grosz’s early satirical drawings are more overtly political than Pascin, notably in his representation of social life in Berlin during the period of the Wilhelmine Empire (1890-1918).

And if one looks closely at his pre-war drawings of vulgarity and violence, one realizes that, with a few exceptions, the appearance of the caricatured types cannot be identified by specific class characteristics, but rather that they reflect distorted traits of brutes and demons. … Then came the war … He condemns the charlatans of all kinds who conspired towards this war, businessmen, clergy, poets, military officers and fat bourgeois alike. (Knust 223-224)

Grosz’s drawing Das Ende des Weges (Aus Nahrungssorgen) [The End of the Road (Out of Fear of Starvation)] (1913) is a brutal depiction of a family driven to suicide by abject poverty.

Grosz had before the outbreak of WWI already developed a more violent satirical form of representation than Pascin. In Phantastische Gebete, Grosz depicts the drunken excesses of the bourgeois (21) and the callous alliance between the military and businessmen (27).

Conclusion

It is hard to imagine two more different artists than Grosz and Pascin in terms of thematic and style, and yet Grosz admired the facility and fluidity of Pascin’s draftsmanship. While there is no discernible influence of Grosz on Pascin’s work, indeed Pascin remained stylistically relatively static, Grosz in his early drawings reveals a compositional and thematic debt to Pascin, notably from Pascin’s drawings for Simplicissimus from 1905 to 1914, arguably his most enduring artistic contribution, albeit an influence that dissipated as Grosz developed his mature style.

Works Cited

Ankum von, Katherina, editor. Women in the Metropolis Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture, U. of California Press, 1997.

Boetzkes, Amanda. Berlin in Disorder: The Representation of Nature in the Works of George Grosz. MA thesis. McGill U., 2002.

Connelly, Frances S. The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture: The Image at Play. Cambridge UP, 2014.

Flavell, Kay. “Über alles die Liebe: Food, Sex, and Money in the work of George Grosz.” J. of European Studies, XIII, 1983, pp. 268-288.

Galerie Flechtheim. List of artists represented: http://alfredflechtheim.com/en/artists/uebersicht/

Grosz, George. George Grosz: An Autobiography. Translated by Nora Hodges, Macmillan, 1983.

Hemin, Yves et al. (Editors). Pascin: Catalogue raisonné, Vol III. English translation by Susan Bauchner-Charlas, Abel Rambert, 1990.

Huselbenbeck, Richard. Phantastiche Gebete. Illustrations by George Grosz, Malik, 1920.

Knust, Herbert. “George Grosz: Literature and Caricature.” Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, 1975, pp. 218–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40246134. Accessed 28 Jun. 2022.

Lévy-Kuentz, Stéphan. Pascin, La Différence, 1989.

Lewis, Beth Irwin. “Lustmord: Inside the Windows of the Metropolis.” Berlin: Culture and Metropolis, edited by Charles W. Haxthausen and Heidrun Suhr, NED-New edition, University of Minnesota Press, 1990, pp. 111–40.

Loosli, Michael. “The Kallikantzari – An Image in Nikos Gatsos’ Amorgos.” Modern Greek Studies (Australia & New Zealand), Volume 10, 2002, pp. 125-128.

Schneede, Uwe. George Grosz: Leben und Werke. Gert Hatje, 1975.

---. George Grosz: His Life and Work. Translated by Susanne Flatauer, Universe Books, 1979.

Simplicissimus. http://www.simplicissimus.info/index.php?id=5.

Jill Suzanne Smith, Berlin Coquette: Prostitution and the New German Woman, 1890-1933, Cornell UP, 2013.

Tatar, Maria. Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princetown UP, 1995.

Tsampouraki, Alkistis. “George Grosz's Lustmord images: Misanthropy and Trauma in the Eve of the War.” MA Thesis, UCL, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/.

[1] Born Julius Mordecai Pincus.

[2] Born Georg Ehrenfried Groß.

[3] “By 1930 Grosz had abandoned a brief commitment to Communism and rejoined the ranks of the cultural pessimists” (Flavell 268).

[4] For the collection of Grossmann’s works in the MOMA, see: https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-2372_thumbs.html?utm_source=pocket_mylist

[5] Pascin, Grossmann and Grosz were represented by the Galerie Flechtheim with their works exhibited at the Gallery Flechtheim in Dusseldorf and later at its Berlin branch (Flechtheim).

[6] Pascin continued to contribute intermittently to Simplicissimus until 1926.

[7] The first edition of Phantastiche Gebete was published in Zurich in 1916 with woodcut engraving by Hans Arp (1886-1966).

[8] The caption reads: “Wenn nur einer käme und mich mitnähme!” (“If only a man would come and take me away!”) (Hemin 29).

[9] The caption reads: “If Mr Hazenbeck [founder of the Hamburg zoo] refuses our father, we are ruined” (Hemin 18).

[10] The caption reads: ““No one will be foolish enough to doubt that the magical music of family life combined with plastic beauty surpasses in intensity with intoxicating chords the being without soul for the celibate and that it emanates from them melodies upon which the heart can strike its own chords” (Hemin 25).

[11] The caption reads: “So, Mieze, what do you have to say about it? They locked up your Emile for a short year for pimping.” “Thank God, one less mouth to feed!” (Hemin 21) .

[12] The caption reads: “If I still earn as much, I am paying for the studies of my father.” (Hemin 22)

[13] The caption reads: “So, already back from Magdebourg” (Hemin 17).

[14] The caption reads: “”Our rat is quite fat; we are going to kill it now. If we wait until the King’s birthday in the end, the Marshall will come to get it.”

[15] The caption reads: “Are you still painting since you got married?” “What an idea, you know very well that birds no longer sing when they are laying eggs” (Hemin 27). .