New Objectivity and the Portraiture of Christian Schad and Otto Dix

A study comparing two leading German artists representing the New Objectivity style of painting

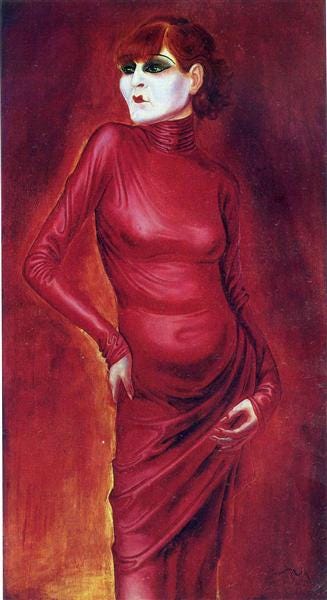

The Dancer Anita Berber. Otto Dix. 1925. WikiArt.

Otto Dix (1891-1969) and Christian Schad (1894-1982) occupied a central place in the development of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) school of painting, and in particular their portraiture. Franz Roh (1890-1965) was instrumental in formulating the intellectual framework for this new direction in painting, notably in his 1925 book Nach-Expressionismus: Magischer Realismus. Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei (‘Magic Realism. Problems of the Most Recent European Painting’).

Both German phrases, Neue Sachlichkeit and Magischer Realismus, then denoted one and the same thing; the difference was only one of emphasis. Both referred to a mode of representation which had come into being “after the disappearance of the Expressionist manner”, and which was “firm in compositional structure but once more representational” (Hartlaub); and both terms were intended to have an application which went beyond contemporary German art. (Schmied 9)

Roh helped Gustav Hartlaub (1884-1963) organise the exhibition Neue Sachlickeit–Deutsche Malerei seit dem Expressionismus, originally planned for the autumn of 1923 but which finally took place from 14 June to 13 September 1925 at the Kunsthalle Mannheim.

The formula Neue Sachlichkeit was originally devised for painting. It was created in 1923 by G.F. Hartlaub, at the time director of the Mannheim Art Gallery, as the title for an exhibition of post-expressionistic objective paintings and graphic arts to be held in that museum. (Schmalenbach 161)

In May 1923, Hartlaub had written a circular letter canvassing names of artists to exhibit.

I wish in the autumn to arrange a medium-sized exhibition of paintings and prints, which could be given the designation “Die neue Sachlichkeit.” I am interested in bringing together representative works of those artists who in the last ten years have neither been impressionistically relaxed nor expressionistically abstract, who have devoted themselves exclusively neither to external sense impressions, nor to pure inner construction. I wish to exhibit those artists who have remained unswerving faithful to positive palpable reality, or who have become faithful to it once more. (qtd. in Schmalenbach 161)

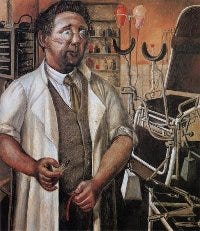

Christian Schad came from a wealthy and well-connected Munich family, Dix from a working-class family, near Gera in Thuringia. Both artists had lived in Berlin: Dix from 1925 to 1927, Schad from 1928 to 1942. Dix left Berlin in 1927 to take up a teaching post at the Akadamie der Bildenden Künste in Dresden, while Schad moved permanently from Vienna to Berlin in April 1928. Both artists exhibited at the exhibition Die Neue Sachlichkeit from March to April 1927 at the Galerie Neuemann-Nierendorf in Berlin run by Karl Nierendorf (1889-1947), who acted as Dix’s agent from 1922 to 1927 and whose portrait Dix painted in 1923. Schad’s Neu Sachlichkeit period ran from Maria und Annunziata vom Hafen, painted in Naples in 1923, throughout the time of his residence in Vienna from 1925 to 1928, and for the period from his phased move to Berlin in 1928, effectively ending with the 1930 portrait Mexicanerin (Storr). The association of Neu Sachlichkeit with the work of Otto Dix started around 1920, with an early example being his portrait Urologen Dr. Hans Kock (1921), and continued until his internal exile under the Nazi regime following his dismissal from his professorial post in Dresden in 1933 (Michalski 53-62).

Dr. Hans Kock (1921)

While Schad was detached and Dix emotionally engaged in their respective approach to representation of the model, they shared a deep understanding of the techniques of oil painting, glazes and the use of tempera grounds; both had studied the Old Masters of the German and Italian Renaissance, reinforced by Dix’s visit to Italy in Winter 1923-1924 and Schad’s residence from 1920 to 1925 in Naples and Rome.

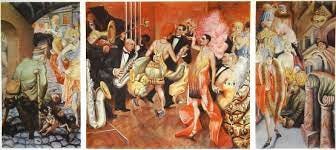

Each artist had experienced the trauma of the First World War and its aftermath in dramatically different ways. From 1915 to 1918 Dix served as a heavy machine gun operator in the trenches in France, with a brief spell from November to December 1917 on the Eastern Front in Belorussia (Schubert 21-32). Schad, a pacifist, went into exile to avoid conscription; first to Zurich in 1915, where he met the writer and Dadaist Walter Serner (1889-1942), whose close friendship Schad remembered in Relative Realitäten: Errinerungen um Walter Serner, and from 1916 until 1920 to Geneva. In Geneva, he participated in several Dadaist events and experimented with the effects of exposing objects on light-sensitive paper, that became known as Schadographs. This fundamental difference in their experience of WWI, the defining event for their generation, led to stark differences in their thematic choices for their paintings in the 1920s. Dix’s key themes during this period focused on the horrors of trench warfare, the disfigurement of war veterans, sexual violence, and the Berlin demi-monde of prostitutes, pimps, and their sailor clients, culminating in his masterwork Großstadt (Triptychon) (1927-8).

Großstadt (Metropolis) (1927-28)

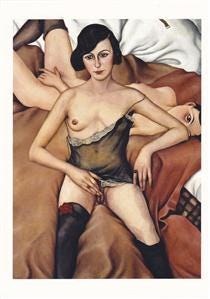

Schad in contrast painted a series of portraits which portrayed individuals isolated from the degradations of social deprivation but imbued with social ennui and languid eroticism, notably in Sonja and Zwei Mädchen, both painted in 1928.

Sonja (1928)

Zwei Mädchen (1928)

Despite their differences, both artists shared an interest in the philosophy of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, both participated in the Dada movement - Dix in the 1920 First International Dada-Messe exhibition in Berlin, Schad in the 1920 Dada Exhibition in the Galerie Néri in Geneva - both flourished in the cultivated and creative environment of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), and both were driven into internal exile and artistic irrelevance by the Nazi’s seizure of power in 1933 (Voermann).

Works Cited

Michalski, Sergiusz. New Objectivity. Benedikt Taschen, 1994.

Schmalenbach, Fritz. “The Term Neue Sachlichkeit.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 22, no. 3, 1940, pp. 161-65. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3046704.

Schmied, Wieland. “Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties.” Translated by David Britt, Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978, pp. 7-32.

Schubert, Dietrich. Otto Dix. Rowohlt, 2014.

Storr, Robert. “Christian Schad and the Neue Sachlichkeit: Of Talent, Ambivalence and the Worst of Times.” Christian Schad and the Neue Sachlichkeit, edited by Jill Lloyd and Michael Peppiatt. W.W. Norton & Company, 2003, pp. 57-69.

Voermann, Ilka. “The Artist as Witness: Otto Dix and Christian Schad.” Otto Dix and the New Objectivity, edited by Nils Büttner, Hatje Cantz, 2013, pp. 36-47.