Paul Delvaux: Trains, Trams and Stations

A study of Delvaux's pictorial engagement with the thematic of the railway

The pictorial and personal fascination with trams and trains of the Belgian surrealist painter Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) has been extensively documented in the 2009 exhibition Paul Delvaux. Peintre des gares at the Liège Grand Curtius Museum and in a series of articles: Régine Rémon’s Un Univers ferroviaire in the catalogue to the 2014 exhibition Paul Delvaux, Le rêveur éveillé at the musée d’Ixelles in Brussels; Denis Laoureux, Un Soir Un Train: les voyages imaginaires de Paul Delvaux, published by Snoeck editions in Paul Delvaux dévoilé (2014); and by Cristina Purcar, “A Fabulous Painting in which I Would Live” Paul Delvaux’s Pictorial Poetic of the Railway Periphery between Art and Urban History.

In the 1920s, Delvaux produced a series of impressionist inspired paintings and drawings of Belgian train stations, in particular of the Gare Bruxelles-Luxembourg, designed by the architect Gustave Jean-Jacques Saintenoy (1832-1892) and opened on 23 August 1854.[1] Only later in his career did Delvaux return to the thematic of tram and railways, but this time from a radically different perspective.

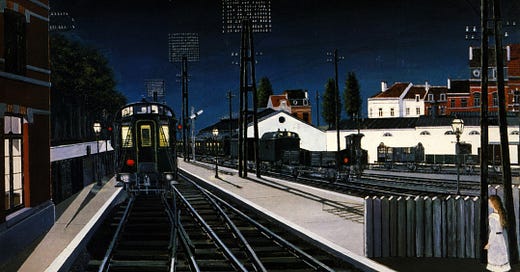

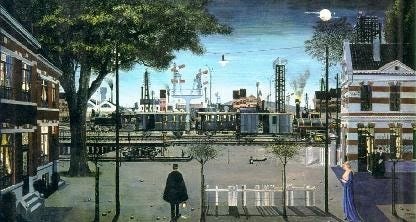

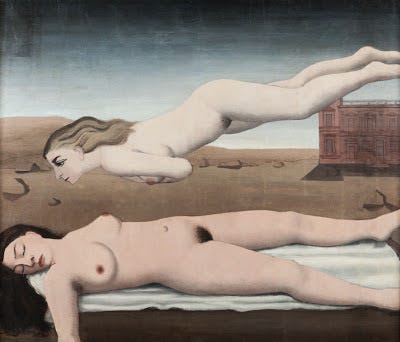

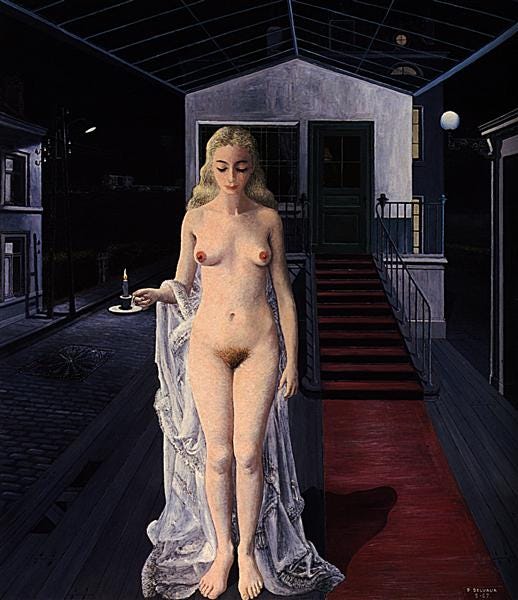

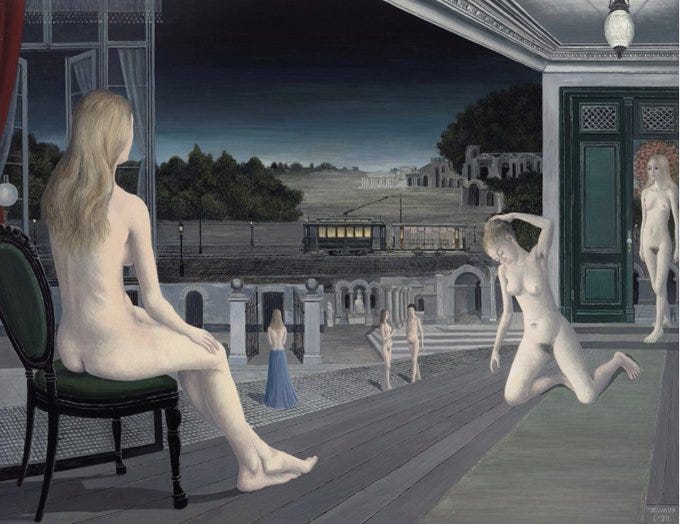

The train station painted by Delvaux at the beginning of the 1920s is therefore, not yet, for him a place of escape open onto every imaginable horizon, but still the noisy, smoke-filled, working landscape of the railway worker. There is here, without doubt, a debt to Constantin Meunier, who died at the height of his fame in 1905. The existence of a style of painting with a social dimension revealing a working environment linked to the industrial way of life extends well beyond the time of Meunier. Where Meunier was interested in the figure of the miner, Delvaux focuses on the railway worker. The latter is not dignified by his work, as was the case with Meunier; it is as if he is dissipated in the flux of the trains which traverse the station. (158) … Delvaux returns to the theme of the railway in 1939. Paintings devoted to rail, however, only multiply after the Second World War. Train de nuit (1947) and L’Âge du fer (1951) are two eloquent and representative examples of the change in the painting of Delvaux after the 1934 exhibition Minotaure. The clouds of smoke spewed out from the funnels of roaring train engines give way to the silent movement of a train, or a tram, on the tracks of the imaginary. From then on, the train illustrates less the industrial world than it invokes a voyage to an unknown elsewhere marked by temples of antiquity and Renaissance palaces. The tram, rarely present at the beginning of the 1920s, from 1946 on becomes the central vehicle of the dream. La Rue aux tramways (1946) and La Voie publique (1948) reveal this development. By the same token, the universe of Delvaux becomes nocturnal. The « moon phases », the title of a series of paintings at the beginning of the 1940s, constitute the terminus of a train moving in the night without a driver or time-table departing from an unknown station. Paintings such as Solitude (1955), Train du soir (1957) and Petite gare la nuit (1959) illustrate the connection which the artist establishes between the train, the voyage towards the unknown and the nocturnal world. (161) … It is striking that Delvaux synthesises in the same painting, on the one hand, an almost “museum-like” view of train engines portrayed with an historical sense of detail and, on the other, an implausible element such as a temple of antiquity built on the edge of the tracks, a naked woman in a waiting-room, an ethereal landscape, an unreal lighting, a little girl frozen on the platform of a station at night. To include a train from the 1920s in a setting from 1960, as in La Gare forestière, is a deliberate anachronism which is part of this approach to representation: the evidence of the real is subjected to a short-circuit introduced by the artist and the image is thereby imbued with mystery. (Laoureux 158-62, my trans.)

Christina Purcar situates Delvaux’s late 1950s and 1960s railway paintings in a site-specific context.

In this paper, a complementary attitude is proposed, suggesting that the imaged places might be read not only as places of the mind, but also as subjective inventories of real places and types of places, pseudo typo-morphological surveys of the specific architectures and urban areas dear to the artist, namely the industrial turn-of-the-century railway-neighbouring peripheries. It is argued that many of Delvaux’s images can be read as architectural capricci, contributing to a specific taste-formation, much like the eighteenth-century capriccio painters contributed to the general appreciation of antique monuments. (68)

In 1954, Delvaux and his wife Anne-Marie de Martelaare (Tam) took up residence at 34a, avenue des Campanules, Boitsfort and remained until 1984, when he moved permanently to Furnes on the Belgian coast (Van Mol 4-7) . Purcar focuses on Delvaux’s representation of the suburban train station at Watermael close to their new residence.

Close-reading works like Faubourg (1961), Le Gardien de Nuit II [The Night Watchman II] (1961)(Fig. 6), Esquisse pour Petite place de gare [Sketch for Small station square] (1962) (Fig. 3), one recognises the small railway station Watermael with its suburban surroundings, albeit differently reconfigured in each painting. In both Faubourg and Le gardien de nuit, the building is truncated of its single-floor side-wing, rendered whitewashed in the former image (it was whitewashed before its restoration), respectively with its characteristic brick-stone stripes in the latter. In Esquisse pour Petite place de gare (Fig. 3) only the ground floor door and its framing are recognisable, the rest of the station building (distinguishable from the houses by its position, adjacent to the railway tracks) being invented. Nevertheless, in a 1985 fresco for a local cultural centre in Watermael-Boitfort, Delvaux rendered the Watermael station in a clearly recognisable manner, however still as part of an invented composition, grouping the most representative edifices of the neighbourhood. When comparing the painting with the actual configuration of the station’s immediate environment (Fig. 5), Delvaux’s strategies of displacement and idealisation become evident. In the “real” situation, it is hard to obtain a well-framed view of both the station building and the neighbouring domestic fronts, from either side of the railway tracks. The images, however, are clearly constructed such as to obtain balanced and harmonious compositions, quasi-symmetrically framed by facades that align along orthogonal axes, whereas in situ, the street pattern is rather irregular. (71-72)

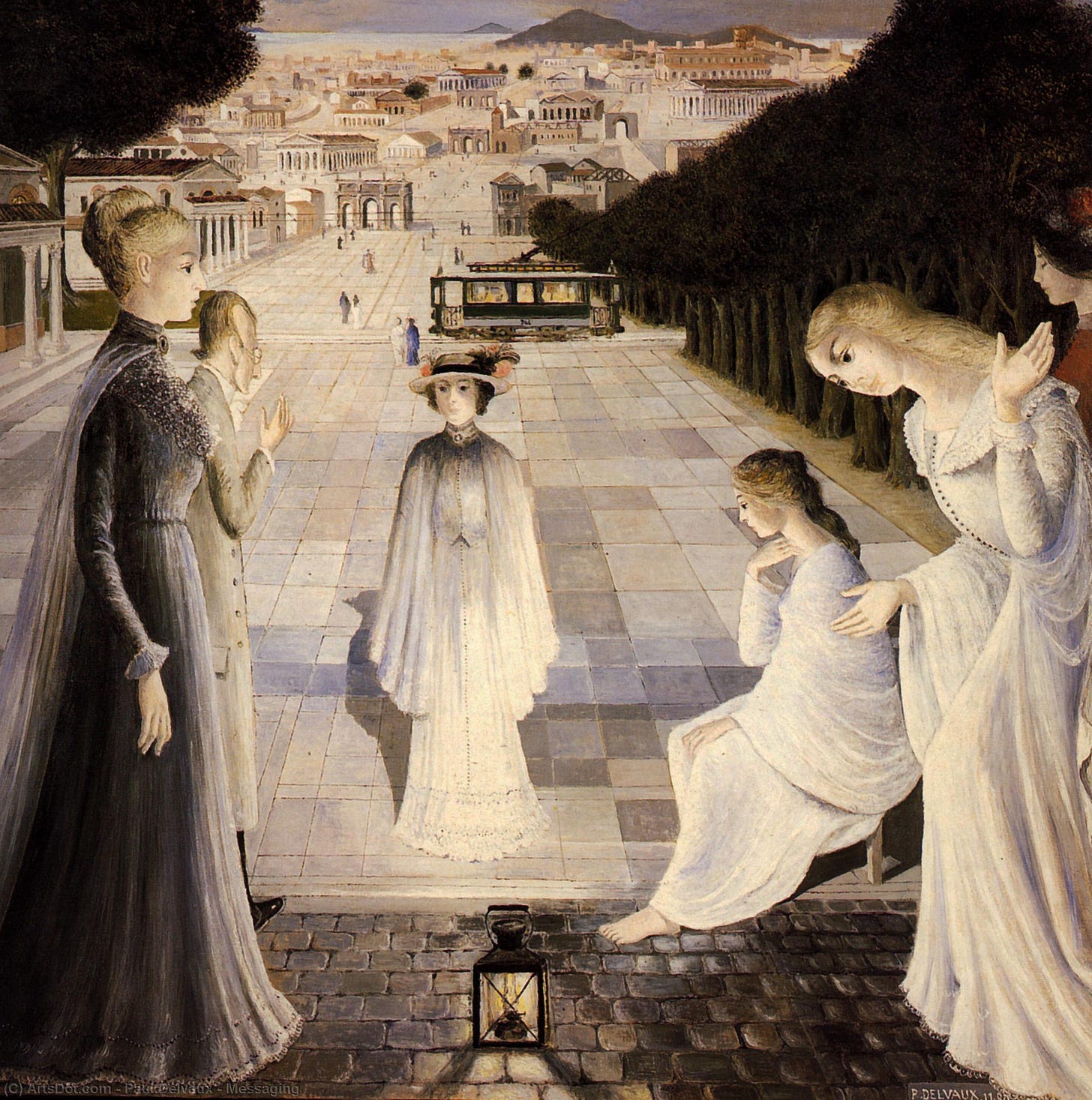

In step with his contemporary René Magritte (1895-1967), with whom Delvaux had participated in a 1923 exhibition for young painters at the gallery Georges Giroux in Brussels, Delvaux created mystery through the realism of pictorial rendering and technical mastery, but he also introduced a sense of subdued eroticism, as in Le Rêve (1935) or L’Annonciation (1955), whereas Magritte at times turned to the grotesque, as in Le Plaisir (1926) (Connelly 9-10).

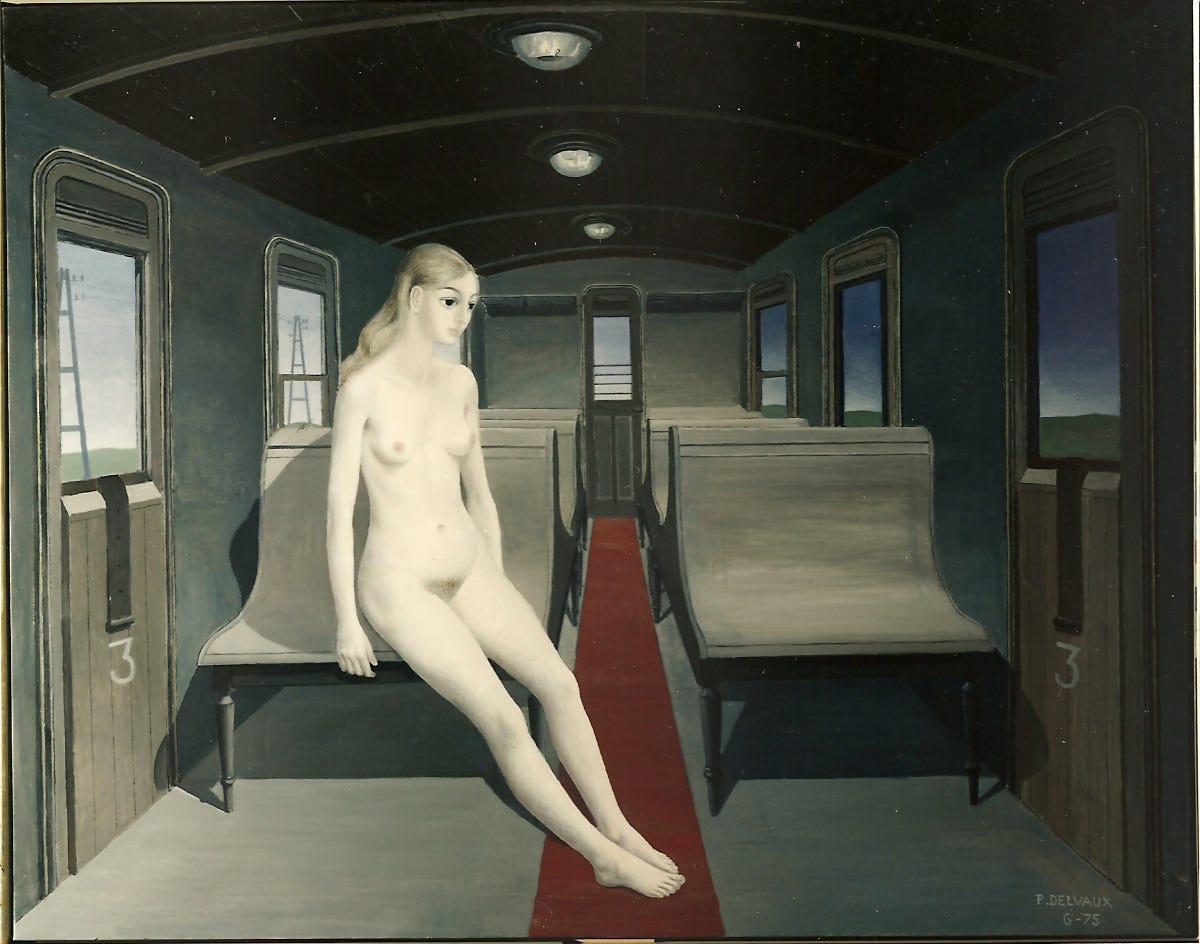

In utilising the railway station and carriage as a setting for creating a pictorial universe, Delvaux drew on his study of the technical minutiae of trains and stations from early on in his career, juxtaposing the architectural order of the train station or carriage with decontextualised nudes and elegantly dressed females that float in and out of the viewer’s consciousness creating a bridge to suppressed memories, as exemplified in Chrysis (1967) and Le dernier wagon (1975)[2].

Dream-like scenes set against a background of classical buildings in perspective, inspired by Georgio de Chirico (1888-1978) whose work Delvaux had seen at the 1934 international surrealist exhibition Minotaure at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (Neve 129), infiltrated a number of Delvaux’s train and tram-themed paintings, including Le soir tombe (1970) and La messagère du soir (1980).

The complexity of the influences on Delvaux’s pictorial universe matched to his technical mastery led to the creation of a series of tram and train-inspired paintings that rank amongst his most impressive works.

Works Cited

Connelly, Frances S. The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture: The Image at Play. Cambridge UP, 2014.

Laoureux, Denis. “Un Soir, un Train: les Voyages Imaginaires de Paul Delvaux.” Paul Delvaux Dévoilé, Musée d’Ixelles-Snoeck, 2014, pp. 155-63.

Neve, Laura. “Un rêve d’Antiquité.” Paul Delvaux: Le rêveur evéillê, Snoeck, 2014,pp. 129-33.

Purcar, Cristina. “A Fabulous Painting in which I Would Live: Paul Delvaux’s Pictorial Poetic of the Railway Periphery between Art and Urban History.” sITA Studies in History and Theroy of Architecture, issue 4, 2016, pp. 66-82.

Rémon, Régine. Paul Delvaux: Peintre de Gares. Luc Pire, 2009.

---. “Un Univers Ferroviare.” Paul Delvaux: Le rêveur evéillê, Snoeck, 2014, pp. 29-36.

Scott, David. Paul Delvaux: Surrealizing the Nude. Reaktion Books, 1992.

Van Mol, Jean-Jacques (editor). Paul Delvaux à Watermael-Boitsfort. Chroniques de Watermael-Boitsfort. Nouvelle serie no. 41, December 2017.

[1] The station was demolished in 2004 to make way for an extension to the European Parliament building with only the facade remaining.

[2] “The contrast between naked and clothed in the sketch [The Suburban Train] is superseded in the painting [Le dernier wagon] by the tension between the nudity of the woman and the blood-red carpet on which her feet lightly rest, a carpet that leads the eye back to the narrow doorway of the carriage in a perspective that as in Pink Bows of nearly forty years before, is the inverse of the one proposed by the triangle of pubic hair between her white thighs” (Scott 119-20).