What does Mayan art and architecture reveal of their civilization?

An overview of Mayan art and civilization

Civilization is defined in the Pocket Oxford Dictionary as an “advanced stage or system of social development”. There is no doubt that Mayan civilization satisfied this definition and that its achievements in such fields as hieroglyphic writing, the Maya Long Count calendar system, mathematics, and astrology[1] matched those of the civilizations of Egypt, China and Mesopotamia. Mayan art and architecture, to date the most successful record of their civilization, reveals the social structure on which it was based.

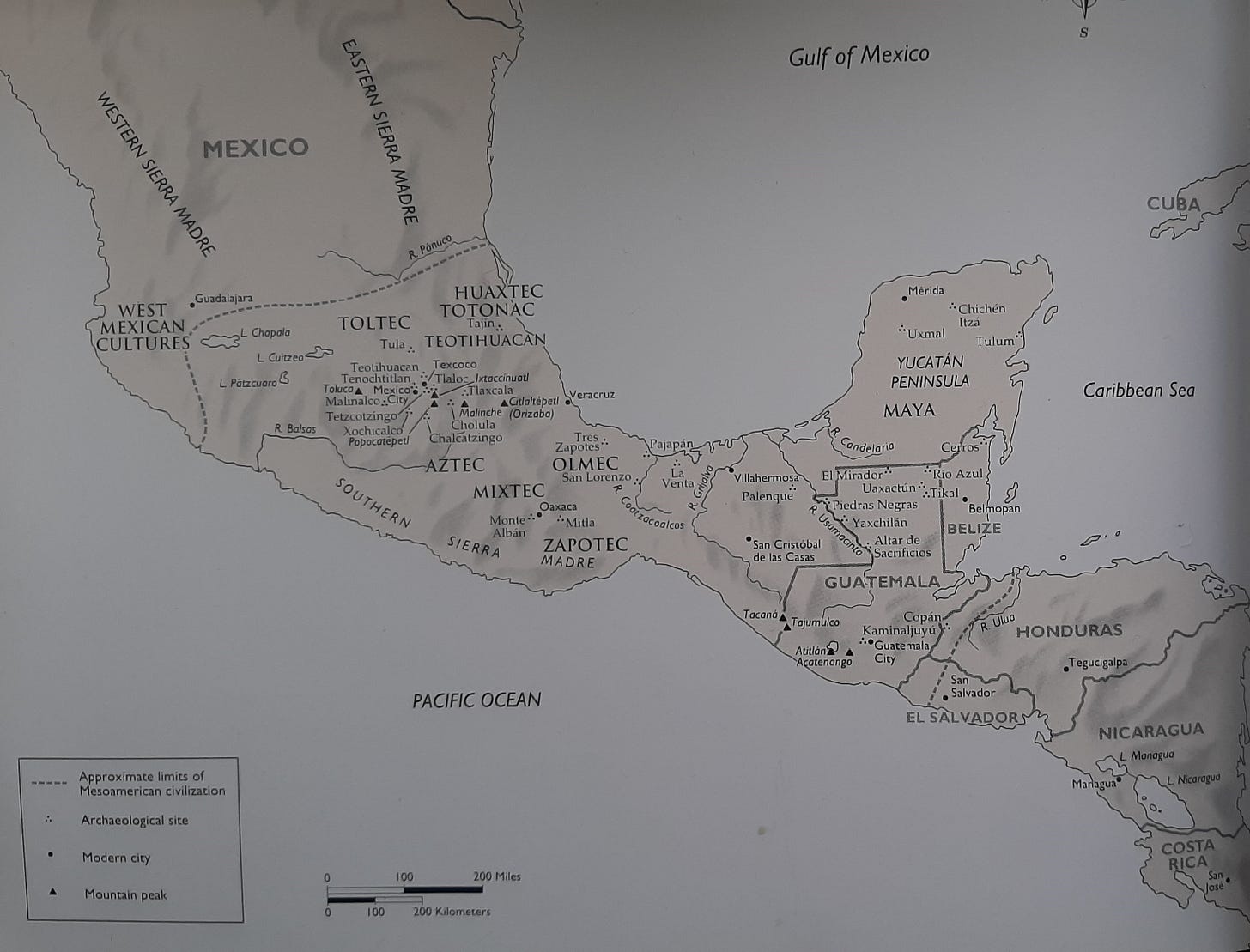

Mayan civilization may be defined in terms of both time and geographic area. Whilst the Mayan race, and their various languages, survive to this day, the principal Mayan achievements in art and architecture belong to the period 350 BC to AD 900,[2] commonly referred to as the Late Preclassical Period (350 BC to AD 150) to the Classic Period AD 150- 900 AD). Geographically, the Maya occupied three separate areas: the southern, highland area which now includes the highlands of Guatemala and adjacent Chiapas together with the Pacific coastal plain and the western half of El Salvador; the central lowland area which includes the Petén in northern Guatemala, Belize and parts of western Honduras; and the northern lowland area which constitutes the Yucatan, a peninsula now part of Mexico and northern Belize. The central and northern areas, which had no natural barriers between them, constituted the most fertile ground for the full flowering of Mayan civilization.

The Ancient Americas. p. 116

There are two principal types of architectural remains in the classic Mayan era (AD 250-900): the large ceremonial sites such as Tikal and Seibal in the Petén, or Copán in western Honduras and the dwellings of the peasant population which, while infinitely less grandiose, followed the same constructional principles: raised up on stone or earthen mounds to avoid the flooding and based on a simple vaulted roof structure. The two types of structure are usually geographically separated and it is still unclear to what extent the ceremonial centers also served as cities for dwelling. They certainly did not have walls as did their medieval European counterparts and lacked the organizational planning and grid structure associated with great urban sites in Mexico such as Teotihuacan. The typical Mayan ceremonial site consists of a series of stepped platforms topped by masonry superstructures arranged around broad plazas or courtyards. The site is dominated by temple pyramids made from the local limestone covering a rubble core. The temple pyramids contain only few narrow rooms and clearly were not used for habitation. Many of them are the result of continuous overbuilding during the Classic and the Post-Classic period and archaeologists have found the original temple structures beneath subsequent layers. The most dramatic find concerning the temples which has helped explain their function was by the Mexican archaeologist Alberto Ruz in 1952 at the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque near the River Usumacinta. At the base of the palace, he discovered the concealed funerary chamber of the most powerful ruler of the Palenque rulers, King Pacal, who died in AD 683 at the age of eighty. He was buried beneath a huge funerary slab of stone with intricate carvings and inscriptions, together with sacrificial victims and jade carvings of exquisite beauty. This discovery, which had been further substantiated by recent work on the interpretation of Mayan stelae inscriptions describing the achievements of the ruling kings, indicates that the temples, like the Egyptian pyramids, served as monuments to the ruling monarchs.

Palenque. Temple of the Inscriptions. Wikimedia.

In addition to the temples, much of the ceremonial site is typically taken up by a collection of palaces with a large number of internal plastered rooms and interior courtyards. Magnificent examples of these structures may be found at the Nunnery Quadrangle and at the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal in the Puuc hills of the Yucatan region. The purpose of these buildings is unclear. They may have served as dwelling quarters for the nobility, although the rooms seem unnecessarily cramped, or they may have been the equivalent of monasteries used for religious purposes. In the plaza area around the main buildings, up to the end of the classic Mayan civilization by AD 900, there have been found inscribed free-standing stelae. The subject-matter of the stelae is always the same: a depiction of the contemporary ruler wielding a symbol of his authority, such as a scepter, and trampling a captive underfoot. The stelae also have inscribed on them the date in the Mayan long count and glyphs which have been deciphered as recording the main achievements, mostly of a military nature, of the ruler’s reign. Finally, there is at many Mayan sites, as throughout Mesoamerica and pre-Columbian sites, a ball court which from surviving reliefs and artefacts was clearly a major focus of Mayan social life.

Mayan stelae from Copan (Honduras). Frans-Banja Mulder. Wikimedia.

Ballcourt at Cobá. Ken Thomas. Wikimedia.

In contrast, the picture gained from archaeological evidence of the basic dwelling unit for the Mayan population is one of simplicity and decentralization. The dwellings tended to be located near the fields of maize and beans that they depended upon for food and each had its own kitchen garden in which vegetables and fruit trees were grown. The distribution of Mayan pottery, jade and other artefacts suggest that intense trade took place throughout the Mayan area during the classic Maya period and with other regions of Mesoamerica. Some of the main ceremonial centers did contain on the perimeters a number of dwelling houses, and in some cases such as Tikal the estimated population rises as high as 40,000.

Mayan architecture thus reveals a civilization which was prepared to divert an enormous proportion of its resources, some estimates suggest up to 60% of GNP at the height of the classical period, to constructing public works. The fact that the principle focus of this effort was the glorification of the city's ruler, and through him the Mayan gods, suggest that Mayan society was rigidly hierarchical with a small elite dominating the majority of the population, The relative similarity of the types of structure found throughout the classic Maya area also suggest that Mayan civilization was homogeneous to a considerable degree and contained a common system of beliefs and social organization. Clearly, the construction of such massive buildings required the accumulation of wealth and slave labor on a massive scale and this is corroborated by the many friezes and reliefs which depict the military activities of the Mayan ruling families and the prisoners captured as a result. The most likely pattern is of a series of regional states grouped around a central ceremonial center with alliances and frequent wars with neighboring states.

The picture of classic Mayan civilization left by architecture remains is reinforced but also deepened by their artistic creations. Classic Mayan artists work primarily in stone, wood, clay and semi-precious stones such as jade. The use of metal was not practised. The artistic objectives that have survived include a variety of monumental sculptures, reliefs and stelae that adorned the ceremonial buildings and surrounding squares, examples of painted frescoes at Bonampak, statuettes in burial chambers and ‘sacrificial wells,’ ceramic statuettes and vessels and rare surviving examples of illustrated Mayan text written on long strips of bark paper folded like screens and covered with gesso.

Earlier classic Mayan art shows strong influence from the surrounding Mesoamerican civilizations. The southern area, centered on Kaminaljuyu in the modern suburbs of Guatemala city, already in the early classic era had fallen under the influence of the powerful Mexican city of Teotihuaca and much of the extensive pottery and statuettes discovered are in fact directly imported. In addition strong influences from the earlier Olmec civilization, such as the long count and the monumental sculpture, and the Izapan civilization, based along the Pacific Coast of Guatemala, have been detected. From these diverse influences, the Mayan artist developed a cohesive style in the middle and northern region based on a delicate narrative technique in stone and ceramic which was used to relate the full gamut of social life, from the dramatic event of a ruler's reign to the exotic collection of Mayan gods and devils and to scenes of everyday life.

The distinctiveness of the Mayan artistic style supports the archaeological evidence discussed above that Mayan civilization, despite its geographical diversity and apparent lack of a central state structure, was remarkably homogeneous. In addition, the quality of the carvings and few paintings that have survived attest to a society that had the resources to support a considerable artistic class and was sufficiently refined in its taste to appreciate their skill. When added to the archaeological evidence of the existence of a number of competing regional centers based around a ceremonial centre and the extraordinary development of thought in the fields of astrology, arithmetic and writing, obvious parallels then exist with the flowering of culture that occurred in classical Greece in the 5th century BC.

Bibliography

Miller, Mary Ellen. “The Image of People and Nature in Classic Maya Art and Architecture.” Richard F. Townsend (Ed.), The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes, Prestel, 1992, pp. 159-170.

Reents-Budet, Dorie. “The Ancient Maya”. Ancient American Art: 3500 BC -AD 1532: Masterworks of the Pre-Columbian Era. 5 Continents, 2011, pp. 101-128.

Valdés, Juan Antonio. “The Beginnings of Preclassic Maya Art and Architecture.” Richard F. Townsend (Ed.), The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes, Prestel, 1992, pp. 147-158.

[1] See Dorie Reents-Budet, “The Ancient Maya”, pp. 103-104.

[2] The dating of these periods is approximate and varies between academics. The dates cited are taken from Reents-Budet, pp. 103-106.